“The ‘One Village One Surname’ phenomenon is prevalent in the majority of Chinese villages. However, due to my familiarity primarily with the regions of Hunan and Guangdong where I have lived, I mistakenly believed until the age of 35 that only traditional Han border areas such as Guangdong and Fujian retained this pattern of population distribution. It was only during recent discussions with colleagues and other friends from Hunan that I realized I had been laboring under a significant misunderstanding about this issue.

One Village One Surname System

In rural China, many villages are characterized by the presence of only one surname, a situation closely tied to China’s ancient clan system and traditional cultural practices of communal living by clans.

Clan System

Agriculture-based ancient Chinese society saw families and clans playing a pivotal role in the social structure. The clan system emphasized the importance of blood ties, with people of the same surname typically believed to share a common ancestor. Consequently, they lived together, jointly upholding familial honor and interests.Land System

In feudal times, land was a crucial communal asset of the family. Members of the same surname worked the land together, fostering close economic cooperation. This economic collaboration also led to their residential aggregation.Marriage Customs

Traditionally, intermarriage between men and women of the same village was discouraged, leading to the concentration of surnames within villages. Marriages often took place between individuals from different villages, further reinforcing the One Village One Surname phenomenon.Social Stability

Residential proximity of members of the same clan helped form a stable social structure. In ancient times, such structures were beneficial for withstanding external threats and facilitated effective social management and order maintenance within the community.Cultural and Religious Activities

The clan system also involved the worship of common ancestors, with clan members participating in rituals together. These activities deepened the bonds among members and fostered the One Village One Surname residential pattern.Historical Migrations

Throughout history, due to war, disasters, and other causes, some clans migrated collectively to new areas. They often established villages there, naming them after their family surname, thereby creating the One Village One Surname layout.

Causes of the Misconception

- Factor of Birthplace

The reason why I held this misconception for 35 years, failing to recognize the common situation in rural China, is mainly related to my birthplace. I was born in a remote mountainous area in central Hunan, where within a few hundred meters of my home, according to the organizational structure of Chinese villages, belonged to the same village group. This village group had about 20 families, totaling around 70 people. However, these 20 families had 8 different surnames, with the most populous surname represented by only a few families. These surnames include Zeng, Peng, Qin, Zhou, He, Xie, Yu, and Wang, among others.

- General Situation in Hometown

If the map is expanded to cover our entire village, about 2 square kilometers (approximately 600 people), the distribution of surnames is even more extensive. Even though I have been away from my hometown for nearly 18 years, I still remember many family surnames in the village. In addition to the 8 surnames mentioned above, there were at least the following surnames in our village: Sun, Hu, Jiang, Song, Ge, Qu, Chen, Xiong, Liao, Liu, Li, Long, Zhu, Su, Lei, Zuo, and Chen, among others. If one were to consult the household registration records, there should actually be more than 30 surnames.

Historical Reasons

According to my family genealogy, our He ancestors migrated from Taihe County, Jiangxi, to Xiangxiang County, Hunan, in 924 AD, and then spread out in Hunan, forming the largest settlement area of the He surname in all of China. According to the 2021 China Name Report released by the Public Security Ministry’s Household Registration Management Research Center, Hunan has become the province with the largest distribution of the He surname, accounting for about 15.3% of the total He population in China. Since I have lived in Hunan and Guangdong for a long time, it was natural for me to compare the two and assume that the history of surname formation in Hunan, like that of our He surname, spanned over a thousand years, while most village families in Guangdong were formed by immigrants in the mid to late 15th century during the Ming Dynasty. This naturally led to a situation where one area had villages with mixed surnames, while the other had villages with uniform surnames.Media Reasons

In general public opinion and media impression, Guangdong and Fujian are considered to be the places where the “clan power” is most preserved in China. When it comes to the “clan” issue, I immediately think of the “One Village One Surname” phenomenon and believe that the strong clan atmosphere in Guangdong and Fujian is caused by this issue.

The Truman Show

Show It was only after learning from many friends from Hunan and other provinces that I realized the “One Village One Surname” phenomenon is indeed the reality in most rural areas across China, including in Hunan. This came as a surprise, giving me a sense of “I was the clown all along.” If “One Village One Surname” is the norm, then my hometown seems to be an exception.

Administrative Division Issue: I was born in Shuangfeng County, Hunan, but this county is relatively new, established only in 1953, with a history of just 70 years. For nearly 2,000 years, from 3 BC to 1953, Shuangfeng County was part of Xiangxiang County. I have consulted the “Annals of Shuangfeng County” multiple times but never found any content indicating a special situation regarding surname distribution. It was only when comparing the “Annals of Shuangfeng County” with the sections on surnames in the “Annals of Nanhai County,” “Annals of Zhongshan County,” and “Annals of Panyu County” in Guangdong that I discovered Shuangfeng County indeed has significantly more surnames than these counties in Guangdong.

Analysis of Causes

After confirming the uniqueness of surname distribution in my hometown, I was initially skeptical of this conclusion. Shuangfeng is an ordinary county in Hunan, geographically located in the central part of the province, and there is nothing special about it among the more than 100 county-level administrative regions in Hunan. The only thing that struck me as different is that Shuangfeng was the birthplace of the most important historical figure in modern Hunan history: Zeng Guofan. Therefore, in researching this issue, I focused most of my efforts on matters related to him.

In fact, since Zeng Guofan’s residence is less than two kilometers from my home, I grew up listening to stories about him. When the clues pointed to something related to him, I already guessed the conclusion: the aftermath of war.

The Qing Government’s Local Disbandment Policy

After the Opium War broke out, Western powers successively invaded China. To counter imperialism, the Qing government organized a large number of soldiers in Hunan to participate in the war. However, after the Opium War ended, as the conflict subsided, the Qing government adopted a policy of disbanding locally the soldiers recruited from southern provinces, including Hunan, leading to a large number of demobilized soldiers and deserters scattering far from their homes.The Taiping Rebellion

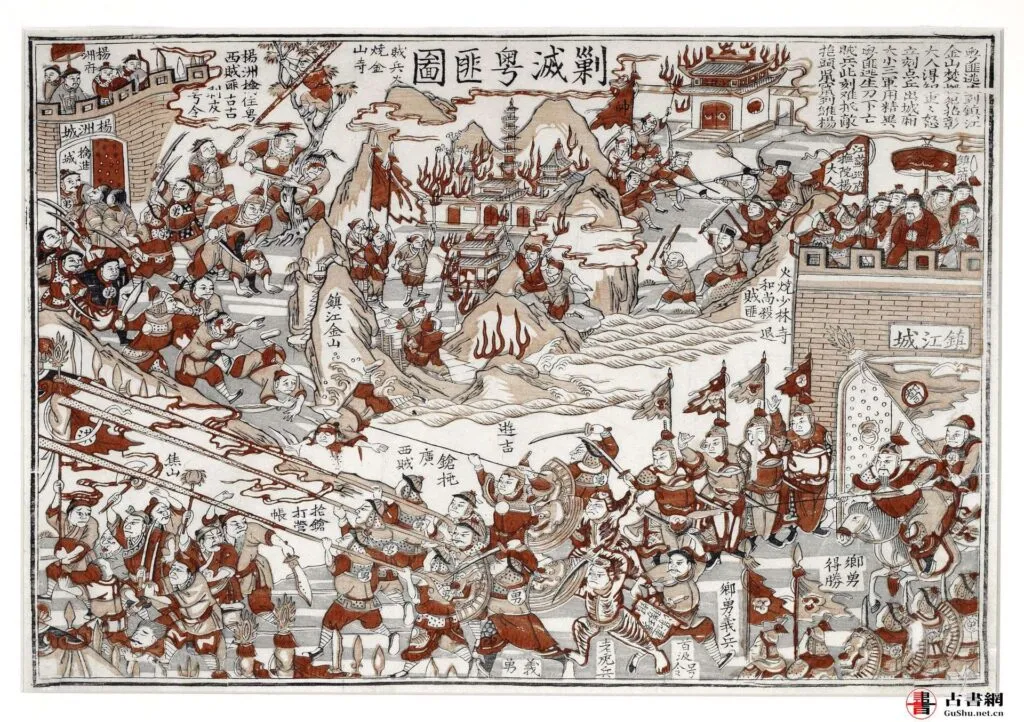

In June 1852, the Taiping Army entered Hunan from Guangxi, under the banner of Christianity, calling on the poor and oppressed to join the Taiping forces and share in the peace of the realm. Many people from Hunan joined the Taiping Army. Within less than a year, the Taiping Army entered and left Hunan four times, affecting more than 60 counties. Starting with less than 10,000 troops when they first entered Hunan, they had grown to a 150,000-strong army by the time they left. Most of the Hunanese who joined the Taiping Army, except for those who defected to the Xiang Army, met with a doomed fate.After the Taiping Army entered Hunan, it inflicted devastating damage on the clan system in the province (from “A Study of Hunan’s Clan System in Modern Times” by Tan Jianguo)

They opposed the worship of ancestors, demanding that people believe in the only true God, the “Heavenly Father,” and recklessly burned and destroyed ancestral halls and the spirit tablets of ancestors. As Zeng Guofan said, wherever the Taiping Army went, “no temple was left unburned, no image untouched.” For instance, after Jiahe County was captured by the Taiping Army, “the city was left in ruins, and the school, examination pavilions, and village ancestral halls, as well as nunneries, were all destroyed.”

They severely cracked down on and suppressed clan militias that opposed the Taiping Army. Many clans in Hunan organized militias and built fortifications to protect themselves and resist the Taiping Army after it entered the province. Some clans even led their members to encircle and annihilate the Taiping Army. Numerous clan militias suffered heavy casualties in battles with the Taiping Army, severely damaging their vitality, and some were even completely wiped out. For example, the landlord Cao Kuilong led his able-bodied clansmen to annihilate the Taiping Army but was subsequently destroyed.

Clan members were either abducted, brutally killed, or forced to flee and scatter. Records of such events can be found frequently in local chronicles. For instance, in Jiahe County, “over a hundred members from two clans were abducted, and thousands were abducted in the entire county. Although some have gradually returned, a quarter of them have not.” After Dong’an City fell, the Taiping Army “slaughtered over a thousand men and women in the city.” In Chenzhou, the Taiping Army “occupied the area, massacring mercilessly. Many abducted residents did not return, and entire villages were reduced to ashes, with nearly every household deserted.” As such, the clan system and clan power suffered a severe blow in this tumultuous revolutionary movement, beginning their decline.

Establishment of the Xiang Army

Zeng Guofan was born in Xingle Township, Hetang, Xiangxiang County, Changsha Prefecture, Hunan, which is now part of Shuangfeng County’s Heye Town. In the process of establishing the Xiang Army, he recruited a large number of locals as soldiers. For example, when setting up the Xiang Army’s naval force, Zeng Guofan required that “the sailors must number four thousand, all from Xiangxiang County, without the use of soldiers from other counties.” His brother, Zeng Guoquan, recruited people exclusively from Xiangxiang County, and even more specifically, from the area within ten miles of their home. From 1853 to 1869, nearly 100,000 people from Xiangxiang County joined the Xiang Army, with the number of officers reaching 7,886. Given that the entire population of Xiangxiang County was less than 500,000 at the time, almost every household had members who enlisted, and Heye Town, where my family is from (then part of Xiangxiang County’s Hetang 24th District), had the highest enlistment rate in the county. For instance, four out of Zeng Guofan’s five brothers joined the military.

According to the “Xiangxiang County Annals” of the Tongzhi era, from the third year of the Xianfeng reign to the eighth year of the Tongzhi reign (1853–1869), there were a total of 7,886 generals from Xiangxiang County. These generals were divided into two categories: civil officials with military achievements, including governors, lieutenant governors, provincial administrators, provincial inspectors, circuit intendants, prefects, salt commissioners, directors of medical services, associate prefects, prefects, associate magistrates, magistrates, and assistant magistrates, totaling 358 people; and military officials with military achievements, including military governors, commanding generals, lieutenant generals, colonels, brigadiers, regimental commanders, battalion commanders, company commanders, and platoon leaders, totaling 7,528 people. Among them, there were 8 governors and lieutenant governors, 39 provincial administrators, inspectors, and circuit intendants, 283 prefects, magistrates, and assistant magistrates, 183 military governors, 417 commanding generals, and 1,132 lieutenant generals and colonels. The Tongzhi annals also recorded 21,335 volunteer soldiers who died in battle or from illness.

- Conquest of Eighteen Provinces

As the most legendary traditional army in modern Chinese history, the Xiang Army played a pivotal role in the development of Chinese history, with half of modern Chinese history having some connection to the Xiang Army, especially for Hunan. The emergence of the Xiang Army brought Hunan, a place that had been obscure for thousands of years, to the forefront, creating countless heroic stories. For example, Mao Zedong’s father joined the Xiang Army founded by Zeng Guofan.

In the second half of the 19th century, the mark of the Xiang Army was left across China, with Xiangxiang County even boasting the achievement of “one county’s soldiers conquering eighteen provinces.” It was during the years of continuous warfare that my hometown began to see a large number of empty-nest families, inevitably leading to increased internal migration to fill the population gap caused by war. Additionally, some soldiers and officers of the Xiang Army who followed Zeng Guofan’s brothers settled here, further complicating the local distribution of surnames.

Quelling the Taiping Rebellion: In 1852, to resist the Taiping Rebellion, Zeng Guofan began to organize the Xiang Army. Over the course of 12 years until the rebellion was quelled in 1864, the Xiang Army mostly suffered defeats and was known as “frequently defeated in battle, yet repeatedly returning to fight.” Countless Xiang Army soldiers died or were wounded during this period.

Quelling the Nian Rebellion :After the failure of the Taiping Rebellion, some of the Xiang Army was disbanded and returned to their hometowns, but a portion continued to serve. For instance, in 1867 (the sixth year of the Tongzhi reign), the Xiang Army suffered a surprise attack by the Nian Army in Qishui County, Hubei, resulting in the death of 5,281 soldiers, including the maternal grandfather of Cai Hesen (one of the founders of the Communist Party of China).

The Lüqiao Incident:In 1874 (the 13th year of the Tongzhi reign), a Ryukyu fishing boat was stranded in Taiwan due to a typhoon and conflicts arose with the local Gaoshan people, resulting in the death of 54 Ryukyu fishermen. Japan used this incident as a pretext to send 3,000 soldiers to invade southern Taiwan in May 1874, starting the Japanese invasion of Taiwan. The Xiang Army was ordered to station in Xiamen, ultimately forcing Japan to withdraw from Taiwan.

Reconquest of Xinjiang:In 1876 (the second year of the Guangxu reign), Xiang Army generals Zuo Zongtang and Liu Jintang led troops into Xinjiang, successfully reclaiming the region by January 2, 1878 (the third year of the Guangxu reign). With the Xiang Army as a backdrop, Zeng Guofan’s son, Zeng Jize, successfully negotiated the “Ili Treaty” with Tsarist Russia in 1881 (the seventh year of the Guangxu reign), successfully recovering Ili from Russian control.

The Battle of Tamsui :In October 1884 (the 10th year of the Qing Guangxu reign), during the Sino-French War, the Xiang Army resisted French invasion at Tamsui (now part of New Taipei City), achieving a significant victory for the Qing army in the later stages of the war.

The Victory at Zhennan Pass:In November 1883, with the Yuenan-French situation critical, to strengthen the defense of the Guangxi border, Zuo Zongtang recommended the Xiang Army general Wang Debang to be stationed at the border. Wang Debang recruited Xiang Army soldiers in Hunan to assist Feng Zicai in the Battle of Zhennan Pass, where they defeated the French invaders.

The Battle of Niuzhuang: In 1894, the First Sino-Japanese War broke out. The Huai Army, led by Li Hongzhang, suffered successive defeats from the Battle of Pyongyang, leading to a catastrophic retreat. After experiencing the campaigns against the Taiping, the Nian, as well as the pacification of Xinjiang, the Xiang Army, once again, was brought to the forefront. In the Battle of Niuzhuang, 1,880 Xiang Army soldiers heroically sacrificed themselves, writing the final chapter of the Xiang Army’s history.

Two Additional Questions Needing Clarification

1.How to View the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement is an unavoidable topic in modern Chinese history. Different eras have different views on the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement, and some of these views are incompatible, almost without any intersection points. If we set aside the issue of “Li Xiucheng,” I believe that most people would still evaluate the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement in a more rational manner. A careful study of Hong Xiuquan and the history of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement reveals that it was just another failed case of a peasant uprising, with no substantial difference from the Nian Rebellion. The Christian doctrines employed by the movement, including some sporadic expressions of anti-imperialist nature, were just the inevitable backdrop of that era. However, when it comes to evaluating the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement, things become much more complex once the issue of “Li Xiucheng” is involved. For a long time after Qiao Benyu published “Evaluation of Li Xiucheng’s Autobiography” in 1962, criticizing Li Xiucheng for being “loyal but not loyal,” the issue of Li Xiucheng became a hot topic in the study of modern Chinese history, and it even became the most studied figure in modern history for a time. The research on Li Xiucheng ultimately boils down to a question of political stance. If one takes a liberal stance, Li Xiucheng did indeed guide the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement towards becoming a capitalist country, enough to be revered as a pioneer by liberals; if one takes a classist stance, Li Xiucheng’s betrayal of the peasant revolution is indeed the greatest stain on his life. Especially after he was captured, his attempt to persuade Zeng Guofan to rebel against the Qing dynasty and declare himself emperor can be seen as evidence that the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement still had not escaped the shackles of the old-style peasant uprising, including the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom itself, which was just another failed feudal kingdom.

“Black on white, the evidence is ironclad; Li Xiucheng’s loyalty did not endure, not a lesson to be learned.” – Mao Zedong

“The Heavenly Kingdom relied on the rise of a new talent, Li Xiucheng, to support it, but the rest of its political and military efforts could not match his.” – A Comprehensive History of China

Li Xiucheng was born into a poor peasant family, grew up fighting hunger and cold, joined the God Worshipping Society, participated in the Jintian Uprising, and his entire family joined the ranks. Through the crucible of revolution, he rose from a soldier to the highest commander of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Army. He lived a life of “iron-hearted loyalty,” leaving heroic deeds that moved people to sing and cry. Unfortunately, his country was destroyed, and he was captured. His attempt to use a false surrender tactic, like Jiang Wei, was detrimental to the spirit of revolutionary education. The history is ruthless, and criticism is inevitable, but it is also a pity! – A History of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement is a very dark chapter in Chinese history, and I have always wanted to remain silent about it. Yet, the charm and hardships of the early days of the movement also inspire awe. This movement originated from noble, exaggerated yet distorted ideals, advanced rapidly with strategic movements, threatening the Qing government’s rule. It swept away everything, refusing to rebuild, trying to overthrow the Qing dynasty but unable to rule the country. The Taiping Army committed arson, murder, and looting, causing widespread suffering, and was eventually suppressed by the Qing army and foreign forces. This movement foreshadowed that China needed a true political transformation, to change its closed-door policy, and usher in a new era, becoming a truly civilized and humane nation. – Mou Yat-sen

2.How to View the Xiang Army’s Massacre Problem

The Xiang Army’s massacre problem has always been the biggest stain on the Xiang Army. Indeed, according to contemporary ethics, it is. However, in ancient times, war was indeed that bloody, including the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, without exception. It is only because the historical moment of the Xiang Army’s massacre has reached the 1860s, which is relatively close to the contemporary period, that it seems especially out of the ordinary. Moreover, the location was in Nanjing, and 73 years later, the Japanese invaders committed a horrific massacre there, making it easy to compare the two events. Here, I also don’t want to “wash the dirt,” but it needs to be pointed out that some people vilify the Xiang Army on one hand and glorify the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom on the other, which is either stupidity or malice. Regarding the dark history of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, I will not quote it here, but I will simply quote the views of scholars on this event, along with a few bloody incidents from the same period.

In examining the issue of massive population loss during the Nanjing-Jiangnan war during the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement, the indiscriminate killing, and sometimes even severe killing by both the Taiping Army and the Qing Army were undoubtedly the most important reasons. However, as time passed, regimes changed, and various political factors were considered, the indiscriminate killing committed by both armies had different interpretations in different historical periods. For a long time, due to the legitimacy of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement as a peasant uprising, the indiscriminate killing by the Taiping Army during the Jiangnan war was, to some extent, diluted by its supposed revolutionary nature. At the same time, with the recent academic reinterpretation of the entire late Qing Dynasty history, the serious crimes of indiscriminate killing committed by the Qing Army during the Jiangnan war were, to some extent, intentionally or unintentionally diluted, and the indiscriminate killing during the war was more often attributed to the Taiping Army, while giving full affirmation, even exaggeration, to Zeng Guofan and his Xiang Army in suppressing the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. It can be said that regardless of the focus of research and the positions held, deliberately exaggerating or avoiding the indiscriminate killing and crimes against humanity of one side is not an objective attitude of historical research. Only by seriously considering the advantages of the victorious Qing government in terms of discourse power and the attitudes of Jiangnan gentry towards the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, and further supplementing new historical materials or even new evidence from archaeological excavations to the study of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, can we better restore the historical truth of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement and this brutal war. — Shao Jian: “Discussion on Indiscriminate Killing During the Jiangnan War of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement”

The Tongzhi Shaanxi-Gansu Hui Uprising — Estimated Death Toll of 20 Million: The Tongzhi Hui Rebellion began in 1862 and ended in 1873, lasting for more than a decade before being suppressed by the Qing government. According to the data analysis from “The History of the Population of China, Volume 5: Qing Dynasty” by Fudan University, after the disaster, the population of Shaanxi, originally over 13 million, decreased by 4.66 million, with a loss of 45.8% in the Guanzhong area. The population of Gansu, originally about 19.45 million (which included today’s Gansu, Qinghai, and Ningxia), decreased by 14.55 million. Among them, the Pingliang Prefecture, with an original population of about 2.8 million, suffered a loss of 2.49 million, and the Qingyang Prefecture, with an original population of about 1.41 million, suffered a loss of 1.287 million. Many villages and towns, originally with tens of thousands of people, were almost deserted after the disaster, with no one living within a radius of ten miles.

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Uprising — Estimated Death Toll of 70 Million: :The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom’s armed forces expanded into Guangxi, Hunan, Hubei, Jiangxi, Anhui, Jiangsu, Henan, Shanxi, Zhili, Shandong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Guizhou, Sichuan, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Guangdong provinces, capturing over 600 cities. This sustained, massive uprising movement, which lasted for more than a decade, directly caused an excessive death toll of at least 54 million in Jiangsu, Anhui, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, and Hubei provinces. If we also consider the population losses in other battlefields such as Hunan, Guangxi, Fujian, Sichuan, and other provinces, the population loss caused by the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom War in China would be at least over 100 million, with an excessive death toll directly caused by the war reaching 70 million.

The Guangdong Tujia-Hakka Clashes — Estimated Death Toll of 1 Million: The Guangdong Tujia-Hakka (Cantonese and Hakka) Clashes during the Xianfeng and Tongzhi reigns (1854-1867) is a major historical event that has been largely forgotten or ignored. This conflict originated in the western part of Guangdong, specifically in Heishan, and spread to several counties such as Kaiping, Enping, Gaoming, Xinxing, Xinning, and Yangchun, lasting for over a decade. The clashes resulted in the massacre of over a million people.